Cellulose is the most abundant and broadly distributed organic compound and industrial by-product on Earth. However, despite decades of extensive research, the bottom-up use of cellulose to fabricate 3D objects is still plagued with problems that restrict its practical applications: derivatives with vast polluting effects, use in combination with plastics, lack of scalability and high production cost. Here we demonstrate the general use of cellulose to manufacture large 3D objects. Our approach diverges from the common association of cellulose with green plants and it is inspired by the wall of the fungus-like oomycetes, which is reproduced introducing small amounts of chitin between cellulose fibers. The resulting fungal-like adhesive material(s) (FLAM) are strong, lightweight and inexpensive, and can be molded or processed using woodworking techniques. We believe this first large-scale additive manufacture with ubiquitous biological polymers will be the catalyst for the transition to environmentally benign and circular manufacturing models.

Cellulose and chitin are the first and second most abundant polymers on the surface of the Earth1, and consequently a recurrent topic of research for their potential utilization in manufacture2,3.

Typically, cellulose is associated with plants and chitin with

arthropods, however the natural occurrence of both biopolymers as

structural components broadens to most kingdoms of eukaryota and

bacteria1. Despite their abundance, they rarely coappear in the same organism. One exception of this are certain species of oomycetes4,

a large class of eukaryotic organisms. Oomycetes grow in a mycelial

form as fungi. However, in contrast to fungi which are characterized by a

chitinous wall, oomycetes’ cell walls, and those of their close

relative hyphochytrids, are predominately based on cellulose4,5.

In the last few years, the pathogenic nature of some oomycetes has motivated a meticulous characterization of their wall singularities, as possible targets for disease control6. Those studies have also shed some light on the characteristics of natural structures made of chitin and cellulose. This knowledge has direct application on the development of bioinspired materials. We now know oomycetes are not a homogeneous population but a combination of members with at least three distinctive cell wall types7. While those walls are mostly composed of cellulose, they also contain low concentrations of chitinous polymers, comprising up to a 10% of the cellulose content8. Inspired by this idea we studied the effects on manufacturability of cellulose by the addition of small amounts (<15%) of highly deacetylated chitin (i.e. chitosan) and the influence of the chitinous polymer in the ability of the composite to form three-dimensional structures.

The objective of our research is to apply the principles of the cell wall of fungi and oomycetes to produce a general manufacture system based on three premises: (i) The resulting bioinspired composite must be made by its natural constituents; (ii) Components must be available and abundant in every habitat on earth; (iii) Cost, environmental impact, and scalability must enable generalized use. Due to recent research on the oomycetal walls we know that chitin and cellulose produce structural composites in their natural form6, without being regenerated, and therefore our criteria (i) and (ii) are theoretically possible. Additionally, both molecules are common industrial byproducts with a combined cost in the range of commodity plastic9,10,11,12, being exceptional, and probably unique, biological candidates to fulfill criterion (iii).

Our research focuses on the reproduction of the synergies between molecules in biological composites, and we approach this by artificially associating structural biomolecules in their organization in living systems13. This differs from the two predominant approaches to bioinspired materials, based on the reproduction of natural composites with synthetic materials of known manufacturability, and from transforming natural components to fit in already existing manufacture techniques14. The later, has given rise to cellulose modified to form thermoplastic polymers (celluloid), and regenerated to form films (cellophane) or fibers (rayon). These chemical transformations and dissolutions require strong organic solvents and hazardous pollutants such as acetone, carbon disulfide, and sulfuric acid15. As a result, while some of those variants of cellulose were very popular in the 1970′s, their current use has declined to small niche markets16.

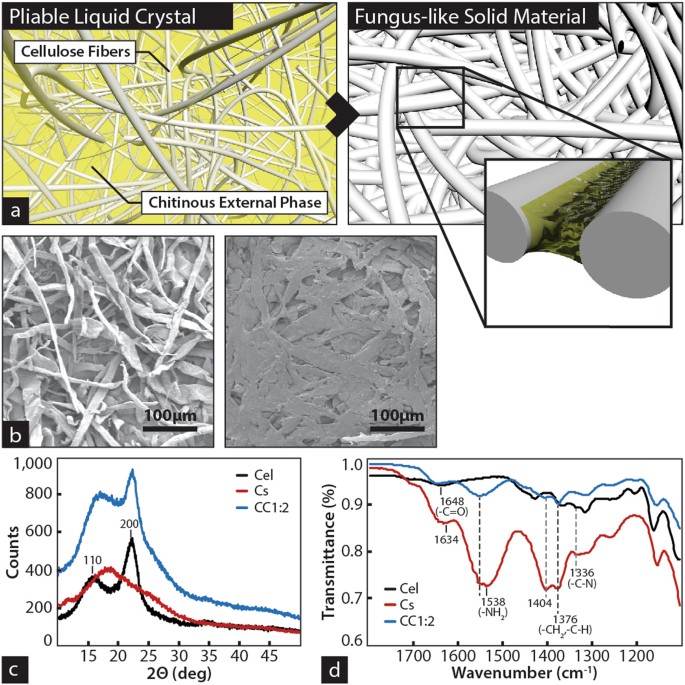

In contrast with the chemical stability of cellulose, chitin with low degree of acetylation (i.e. chitosan) contains enough protonatable groups to enable its dispersion in low concentrations (i.e. 1% v/v) of acetic acid17 (e.g. table vinegar 4–10%). Chitosan in solution is driven into a liquid crystal by partial removal of the intermolecular water18 and in that state we used it as external phase to form colloidal dispersions of cellulose fibers. Further removal of the water molecules results in full crystallization of the chitinous polymer and formation of a solid chitosan-cellulose composite (Fig. 1a). Scanning Electron images reveals the original microscopic fibrous structure of the cellulose in the composite (Fig. 1b), while X-Ray diffraction confirms that the cellulose I crystal conformation19 is intact (Fig. 1c). The FTIR spectra of the chitosan and cellulose composites reveals the predominant interaction between the amino and hydroxyl groups respectively3,20 (Fig. 1d). Separate phases of the two components are observed at large concentration of chitosan, turning into a homogenous composite, without phase separation, but with a single decomposition temperature when the concentration of chitosan is under 30% of the total weight (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 1

We

further explored the manufacturability of the chitin-cellulose

fungus-like material by evaluating the effect of the chitin

concentration on the ability of the composite to reach a pliable state

and retain shape. Chitosan is introduced in the composite as a water

solution. As a result, composites with large amounts of chitosan

(>12%) require removal of part of that water until the material

reaches a state able to conform and retain a three-dimensional shape

(Fig. 2b).

After solidification, composites with low amounts of chitosan (<8%)

show slender mechanical properties, attributable to its inability to

fully bind the cellulose fibers. In contrast, high amounts of chitosan

(>17%) produce strong internal forces as the polymers loses water and

shrinks, undermining the integrity of structure (Fig. 2c).

An inherent optimal ratio of 1:8(w/w) chitosan:cellulose, produces a

pliable composite, where no removal of water is required, with minimum

shrinking and an unexpected low water uptake (Supplementary Fig. 2). Interestingly, recent studies on the oomycete wall draw similar conclusions for the ratios of chitin/cellulose7, and also reported an abnormal water uptake on the cell wall when chitin production is disrupted6.

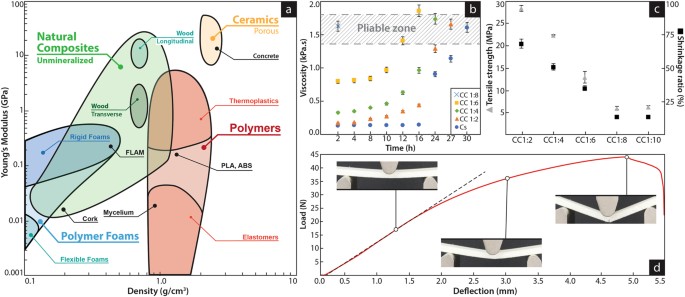

The fungus-like additive material (FLAM) has a cost of about 2 $/kg

and, with a young modulus of 0.26 Gpa and a density of 0.37 g/cm3.

It is wort noting that while the cost of FLAM is in the range of

commodity plastics, is more than ten times lower than those of common

filaments for 3D printing, such as PLA and ABS with an average cost of

20–30 $/kg. The mechanical characteristics of FLAM are within the range

of natural cellulosic composites such as medium to low density woods and

high-density foams, commonly used in product design, construction,

aviation and automotive industries (Fig. 2a,d, Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 2, and Supplementary Movie 1).

Nevertheless, they are significantly different to any characterized

natural material. FLAM is a reproduction of a natural material

synthesized at the microscale (i.e. the oomycete wall), so it is

probable its characteristics are similar to uncharacterized materials

existing only at that scale. The only reported material with almost

identical mechanical characteristics to FLAM is high-ending rigid

polyurethane foam (i.e. pcf-30), commonly used for production of

synthetic bones21.

Figure 2

While

most cellulosic and chitinous natural structures also include other

organic and inorganic components, the interaction between cellulose and

chitosan has proven sufficient to form solid composites. These

interactions are strong enough even in presence of disruptive

components, such as lignin or hemicellulose, enabling the formation of

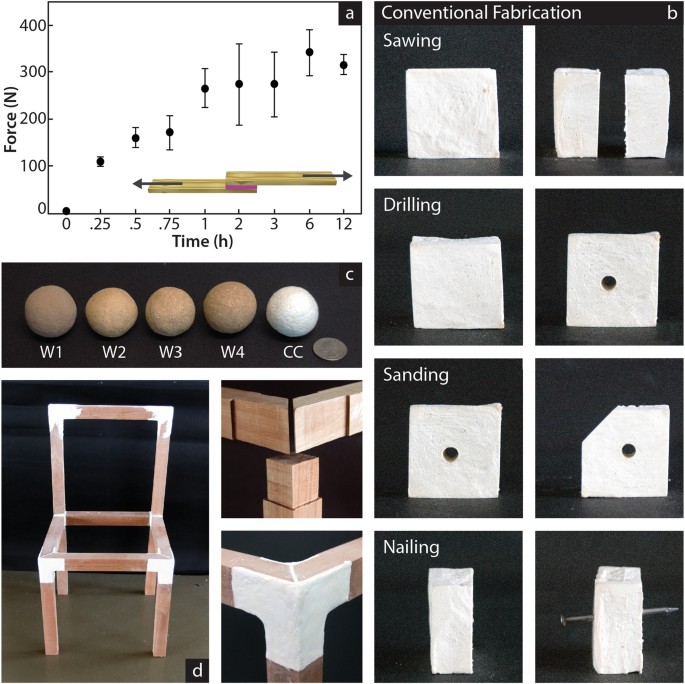

wood flour-based composites (Fig. 3a).

The mechanical characteristics of these wood-based composites are

significantly lower than FLAM based on pure cellulose (Supplementary

Table 2),

yet they enable a generalization of the technology to many other

sources of unprocessed byproducts. In the US for example, 14% of the

municipal waste is wood22,

while industries such as agriculture, food, textile, and paper, produce

high amount of waste with high cellulose content. We tested wood flour

from three different sources and purities, producing composites and

objects with small mechanical differences with respect to the waste

source or the manufacture method (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 3, and Supplementary Table 2).

This chitinous property of binding cellulosic composites is retained by

FLAM as when FLAM is deposited on wood it naturally forms adhesion

bonds able to hold an average of 33.5 ± 7.3 kg per cm2 (Fig. 3a).

This feature broadens the applicability of the material to an

unprecedented range of strategies: it can be machined using common

woodworking techniques such as sawing and sanding, (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Movie 2) as well as used in combination with hardwood and other cellulosic components (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 4, and Supplementary Movie 3).

More interestingly, the property of FLAM to bond with cellulosic

composites also include fusing with itself, enabling its use in additive

manufacturing (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 3

Because

of its abundance and biodegradability, the use of cellulose in a

versatile manufacture approach such as additive manufacturing has broad

technological and economic implications23.

In spite of extensive past and current research to adapt cellulose to

3D printing, progress is still riddled with obstacles such as use of

hazardous solvents16,24,25, lyophilizing small cellulosic scaffolds25 and contamination by mixing the polymer with commodity plastics26,27.

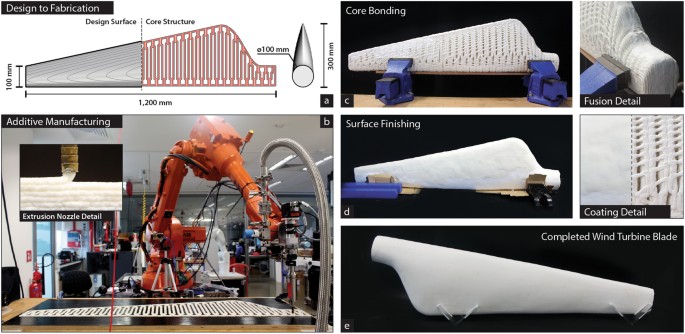

We developed a large scale 3D printing system specific for FLAM natural

materials based on the Direct Ink Writing (DIW) principles28 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figs 3, and 6).

Core components include a precision robotic dispensing system and

associated design-to-manufacture software tailored for FLAM. To

demonstrate the capabilities of the system, we 3D printed a 1.2 m long

wind turbine blade (Fig. 4a). The blade is comprised on two symmetric inner core parts (Fig. 4c)

hollowed to accelerate evaporating hardening and fused together using

FLAM. The tribological function of a turbine blade makes it incompatible

with the stepped surface produced by additive manufacturing29.

To improve surface finish and potential aerodynamic performance, the

blade was coated by a thin layer of FLAM and subsequently polished

(Fig. 4d).

Additional coatings with other materials can be used to add

functionality to the surface, such as self-cleaning, reduced air

resistance, or waterproofing. FLAM has a density less than one half that

of the lightest commercially available 3D printed filament (Polyamide,

0.95 g/cm3), resulting in a lightweight finished blade of 5.28 kg (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Fig. 5, and Supplementary Movie 4).

Figure 4

No

technology has ever been reported to possess the unique characteristics

of FLAM: made of the two most abundant and broadly distributed

components on earth, lightweight, cost in the range of commodity

plastics, suitable for large-scale manufacture, lack of harmful

solvents/pollutants, compatible with cellulosic composites, completely

biodegradable out of composting systems. Additionally, to our knowledge,

there is no other biotic material with the adaptability to be casted,

molded, sanded, sawn and 3D printed. It is expected that FLAM can

delocalize general manufacture and meet the emerging needs of

sustainable manufacture, large-scale fabrication, and circular economy,

as well as be a disruptive technology across multiple industries,

including the architectural, aerospace, and biomedical, enabling the

development of many more areas and new manufacture strategies beyond the

current reach of technology.

In the last few years, the pathogenic nature of some oomycetes has motivated a meticulous characterization of their wall singularities, as possible targets for disease control6. Those studies have also shed some light on the characteristics of natural structures made of chitin and cellulose. This knowledge has direct application on the development of bioinspired materials. We now know oomycetes are not a homogeneous population but a combination of members with at least three distinctive cell wall types7. While those walls are mostly composed of cellulose, they also contain low concentrations of chitinous polymers, comprising up to a 10% of the cellulose content8. Inspired by this idea we studied the effects on manufacturability of cellulose by the addition of small amounts (<15%) of highly deacetylated chitin (i.e. chitosan) and the influence of the chitinous polymer in the ability of the composite to form three-dimensional structures.

The objective of our research is to apply the principles of the cell wall of fungi and oomycetes to produce a general manufacture system based on three premises: (i) The resulting bioinspired composite must be made by its natural constituents; (ii) Components must be available and abundant in every habitat on earth; (iii) Cost, environmental impact, and scalability must enable generalized use. Due to recent research on the oomycetal walls we know that chitin and cellulose produce structural composites in their natural form6, without being regenerated, and therefore our criteria (i) and (ii) are theoretically possible. Additionally, both molecules are common industrial byproducts with a combined cost in the range of commodity plastic9,10,11,12, being exceptional, and probably unique, biological candidates to fulfill criterion (iii).

Our research focuses on the reproduction of the synergies between molecules in biological composites, and we approach this by artificially associating structural biomolecules in their organization in living systems13. This differs from the two predominant approaches to bioinspired materials, based on the reproduction of natural composites with synthetic materials of known manufacturability, and from transforming natural components to fit in already existing manufacture techniques14. The later, has given rise to cellulose modified to form thermoplastic polymers (celluloid), and regenerated to form films (cellophane) or fibers (rayon). These chemical transformations and dissolutions require strong organic solvents and hazardous pollutants such as acetone, carbon disulfide, and sulfuric acid15. As a result, while some of those variants of cellulose were very popular in the 1970′s, their current use has declined to small niche markets16.

In contrast with the chemical stability of cellulose, chitin with low degree of acetylation (i.e. chitosan) contains enough protonatable groups to enable its dispersion in low concentrations (i.e. 1% v/v) of acetic acid17 (e.g. table vinegar 4–10%). Chitosan in solution is driven into a liquid crystal by partial removal of the intermolecular water18 and in that state we used it as external phase to form colloidal dispersions of cellulose fibers. Further removal of the water molecules results in full crystallization of the chitinous polymer and formation of a solid chitosan-cellulose composite (Fig. 1a). Scanning Electron images reveals the original microscopic fibrous structure of the cellulose in the composite (Fig. 1b), while X-Ray diffraction confirms that the cellulose I crystal conformation19 is intact (Fig. 1c). The FTIR spectra of the chitosan and cellulose composites reveals the predominant interaction between the amino and hydroxyl groups respectively3,20 (Fig. 1d). Separate phases of the two components are observed at large concentration of chitosan, turning into a homogenous composite, without phase separation, but with a single decomposition temperature when the concentration of chitosan is under 30% of the total weight (Supplementary Fig. 1).

|

| Mechanical characteristics of fungus-like biomimetic materials. (a) Ashby plot showing the distribution of density and stiffness of natural and synthetic material commonly used in manufacture. Those relevant to this study have been highlighted, while the specific function of the fungus-like bioinspired material reported is labeled as “FLAM”. (b) Viscosity in terms of time for composites of variable amounts of chitosan. The highlighted area represents the range of viscosities suitable for manufacturing techniques, where the material can be extruded, and conform and retain a shape. (c) Determination of the optimal concentration regarding the balance between mechanical properties (tensile strength) and manufacturability (shrinking). (d) 3-point fracture test. Similar to other natural composites, the resulting material is designed for multifunctional structures, balancing strength and stiffness. The 100 × 16 × 6 mm and 3 g FLAM sample shows ductile characteristics; it holds 2.55 kg elastically, after that the internal structure starts to deform, resulting in failure when the load reaches 4.37 kg (Supplementary Movie 1). |

|

| Additive properties of fungus-like materials and their use in woodworking techniques. (a) Adhesion force with respect time following the standard test of adhesion (ASTM D5868) with respect to time. Full strength is achieved after 1 hour, from that point 21 mg of dry FLAM covering an area of 9.3 × 9.3 mm holds the equivalent to 29.02 ± 6.35 kg. This ability of the material to attach to cellulosic composites (included itself) enables its use in additive manufacturing. (b) Use of FLAM in conventional woodworking techniques. A 4 × 4 × 4 cm FLAM cube is sawn in two halves, one of the halves is then drilled and then sanded down to remove one of the corners. A nail is hammered through the other half. (Supplementary Movie 2) (c) Composites made with different sources of cellulosic materials. Samples one to four (from left) are made of wood byproducts of different qualities and sources, while the right sphere (labeled “CC”) is made of pure cellulose (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). (d) Use of the material in combination with pieces of solid wood to produce a functional chair. All pieces are attached uniquely by the FLAM material. The fungus-like biomimetic material can be casted, 3D printed, molded but also modified using regular woodworking techniques (Supplementary Fig. 4). |

|

| Additive manufacture of fungus-like materials. (a) Design of the wind turbine blade fully made of FLAM. The inner core of the blade, built by additive manufacturing, is designed to allow ventilation and reduce weight. The outer shell is produced by coating the core with a 3 mm layer of FLAM. After drying the outer shell is sanded down to produce a smooth surface. (b) FLAM material is dispensed through a 7 mm diameter nozzle to form beads and then layers of material. The pressure is controlled by a closed loop system between a high-pressure tank (1.2 MPa) supplying material and an auger screw before the nozzle. Hot air is focused on the extruded layer just after deposition to accelerate water evaporation. The printing head is mounted on a 20 kg payload six-axis industrial robotic arm with a stationary horizontal reach radius of 1.65 m (Supplementary Fig. 6). (c) FLAM printing of the layers to support the structure of the wind turbine blade. The blade’s core was printed in two halves, each taking about 1 h and 24 h to dry. The average printing speed is of about 50 mm/s and 2.8 cm3 of FLAM per second (Supplementary Movie 3). Two halves of the inner core are assembled together using FLAM as adhesive agent. (d) The blade is coated by a layer of FLAM manually spread over the inner core. Because the ability of the material to be post processed, imperfections can be removed in post-processing stages. (e) After the outer skin is dried, it is sanded down in two steps of decreasing grit. The 1.2 m blade is estimated to be 50% hollow inside and has a weight of 5.28 kg. (Supplementary Movie 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5). |

Click Here to read full article.

0 Comments